|

more about

KARD-TV |

|

|

Wichita, Kansas

and early color television broadcasting |

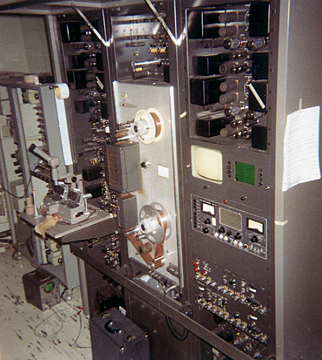

Ampex Corporation, RCA's arch rival in the broadcast video recorder business, owned the rights to the name "Video Tape" at the time, forcing RCA to call their recorders TR's (Television Tape Recorder or TV Tape Recorder) rather than VTR's (Video Tape Recorder). (Ampex lost the rights to the name "Video Tape" in the early 1960's). This is a model TR 2, occupying 3 racks. Note the many vacuum tubes in the days before transistors and other "solid state circuitry" came into wide use. Note the brown oxide tape stock before the days of black magnetic tape. The microscope on the left side of the frame is part of a Smith Splicer - in the days before electronic editing (which is essentially copying selected material in a sequence onto a blank tape), the Smith Splicer allowed precision physical splices to be made. Although motion picture film is also physically spliced, the individual frames are visible to the naked eye through the transparent film base. Video tape images are basically magnetic patterns on an opaque iron oxide base - the early video tape editor played the tape to the edit point, pushed the STOP button, marked the tape with a grease pencil or Magic Marker, carefully unthreaded the tape from the recorder, then gingerly placed the tape on the guides in the Smith Splicer. A "developing fluid" was brushed onto the oxide side of the tape at the grease pencil mark which revealed the magnetic pattern of the recording. The operator located the sync pulse pattern by viewing the "developed" tape through the microscope. A precisely hinged blade made the cut. The freshly cut video tape could then be spliced to the next length of video tape that underwent the same marking, developing, and cutting process. A thin strip of silver mylar splicing tape was applied to connect the ends of tape. (Note the tan gloves the operator wore to keep skin oils off of the videotape). If the sync pulses weren't precisely aligned in the splicer, a nasty picture breakup could occur causing the recorder to become "unlocked" as the splice passed through the head assembly. A good videotape editor in those days was known for splices that didn't unlock or physically fall apart when passing over the spinning headwheel. A characteristic "zing" could be heard when even the best splices passed through the head assembly.

KARD's RCA film island (also known as "film chain"). The tall device in the center of the frame is a multiplexer, which allows multiple film sources such as two 16mm projectors and a slide projector to send their light beams into one or more cameras. The RCA TK-26 color camera on frame right used 3 vidicon pickup tubes unlike the TK-41 studio cameras image orthicon tubes. The light from the projector on the left is directed into the camera by a mirror inside the multiplexer. To direct the image from the projector on the other side of the film chain into the camera, the telecine operator flips the solenoid operated mirrors in the multiplexer. The slide projector (visible in the next photo) could shoot directly into the camera by flipping all the mirrors down out of the way . A concientious master control operator would "go to black" on the video program switcher while the mirror was flipped, but it wasn't uncommon to see sloppy on-air mirror flips between film and slide projectors.

KARD-TV's engineer Ron Jordan at the film island control console. By remote control from the console, the projectors can be started and stopped, slides can be changed (note the round slide carousels), and the multiplexer mirrors can be flipped. The film island operator was a busy guy during live programming. To the right of the slide projector, a smaller black and white camera is located. The TK-26 color camera was on the air only for color films and slides. Neither the NBC network on their affiliates were "full color" in 1964.

An early RCA 2" color "Television Tape Recorder," Model TR-2.